FR

Birthday wishes: Jaroslav Mihule

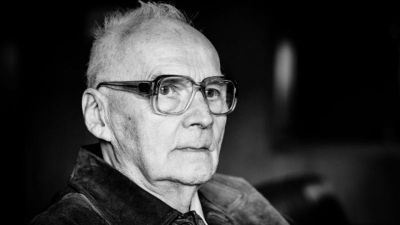

Birthday wishes: Jaroslav Mihule

A wonderful 90-year birthday is being celebrated on 1 December 2020 by the eminent Czech musicologist and Martinů expert, Mr Jaroslav Mihule. His wife, Mrs Alena Mihulová, who has been his closest companion for 65 years, celebrates her own 90th birthday just a week later, on 8 December. Congratulations!

We wish to mark this momentous anniversary by publishing several texts by his contemporaries and admirers.

Jaroslav Mihule 90

/ IVAN ŠTRAUS

In the present time, when we older individuals are secluded, the recollection of personally experienced history may be a therapy that helps overcome the feeling of isolation. One such instance, which could invoke a wealth of images from the past in kindred spirits, is an unassuming little book published by Academia with the bizarre title Tinnitus. Its author, Prof. PhDr. Jaroslav Mihule, CSc., was born 90 years ago. The publication is named after the Latin word for the buzzing and ringing in the ears that mostly affects the elderly due to ageing blood vessels. The unpleasant noise can be alleviated through medication, but it cannot be removed completely. One must learn to live with it. (Speaking from personal experience, it can be done…) Jaroslav Mihule decided to “drown out” the troublesome condition by having to concentrate on writing a testament of his life; a life played out against the backdrop of the historical events he had witnessed.

The effects of history cannot be disentangled from one’s own life. But every biographer – understandably – balances the subjective and historical aspects of memories in his own way. Mihule remains an objective commentator, avoiding pathos when writing subjectively, and steering clear of excessive dramatisation when placing the vagaries of his life in their historical context. I hereby offer a few glimpses of the autobiography as a teaser to the whole book – and its 90-year-old author.

The early solitude caused by his father's death (when Jaroslav was 11) and his mother's post-war departure, in search of new opportunities in the re-settled border regions, together with his thirst for education, both universal and musical, led Mihule's life in a singular direction. His fascination with all types of music won out over the early possibility of becoming a piano virtuoso. After attending the famous Academic Grammar School in Štěpánská Street, Prague, he enrolled at the Prague Conservatoire to study composition and conducting. Although he did not display his political convictions openly, he did not hide them either, which forced him to struggle with the many iniquities of the post-1948 Communist regime. Had he not encountered some important figures exactly when he needed to, his fate might have been much more difficult.

Fortune favoured him with his musical friends, hidden from the public at large, but nevertheless valuable and versatile. Among them were Dr Eduard Herzog, a musicologist with a profound knowledge of the evolution of music from its very beginnings to the birth of so-called New Music, which he helped form in the 1950s and 60s. He guided his eager student through the principles of Schoenberg’s dodecaphonic system and the Second Viennese School, initially so hard to fathom even for many fellow musicians. He also had access to recordings of music from the start of the twentieth century, which the politicised aesthetics of the time suppressed with hatred. In private sessions, Herzog would speak of its various forms to anyone who was interested.

Also important to Mihule was the legendary photographer Josef Sudek, at whose studio the best young musicians and musicologists came together to listen to rare recordings. It was Karel Šebánek, an employee of the Czech Music Fund, who initiated Mihule into the secrets of the music of his close friend Bohuslav Martinů and who helped him build the foundations of his interest in the works of one of the four mainstays of Czech music. Šebánek also introduced him to Martinů's widow, Charlotte. Their professional relationship later grew into a deep friendship that greatly enriched Czech culture.

After finishing his education, the need to earn a living brought Mihule into contact with the gymnastics community and even resulted in compositions for Spartakiad exhibitions. (Who knew that?!!!) His clever penmanship was noticed by various editors, who asked him for insightful articles primarily on the music of Martinů. These culminated in two monographs, one published under totalitarian rule, the other born into a free country. The latter, with its 628 pages and extensive annotations, is a timeless source of information for anyone wanting to learn something about any of Martinů’s compositions. If his friend and colleague of sorts, the Belgian musicologist Harry Halbreich, could – thanks to his freedom to travel the world – create a catalogue of the works of BM (what Köchel is to Mozart – KV – Halbreich is to Martinů – H), we may be all the more grateful to Jaroslav Mihule for providing an alternative perspective on Martinů’s oeuvre despite the difficult circumstances he was forced to live in for 40 years.

Mihule finished his academic career as a prorector at Charles University – the post a fitting reward for a demanding lifeplaced at the service of Czech culture. Mihule never yielded to the temptations or pressures of the Communist cadres. He bore the consequences and, notwithstanding, delivered a body of work that is one of the building blocks of our nation’s culture. He is now one of the top four global experts on the life and work of Bohuslav Martinů.

I was also enrolled at the Academic Grammar School in Štěpánská Street for one year. My sister studied there four years ahead of me, and she introduced me to some of the senior students. It was not until later that I appreciated the unique atmosphere of the place and the sheer number of brilliant personalities nurtured by the school. Jiří Mellan, the prominent sexologist, recited Wolker’s Sailor’s Ballad by heart at some competition. Jaroslav Mihule took part in a performance of Dvořák’s Slavonic Dances in the original piano duet version at a school concert. MUDr. Milada Barešová became a pre-eminent acupuncturist. Jiří Hráše made a name for himself as an excellent director at Czech Radio. Others, from different years: Josef Koutecký, Martin Turnovský, Jan Klusák, Ivan Vyskočil – every name well-known. Even our junior first-year class – from which we were relegated by Minister Nejedlý’s Soviet-style school reform to a town school where we were a ridiculed and proscribed minority – yielded several world-class individuals. Edvard Outrata came to the head of the Czech Statistical Office upon returning from Canada after the Velvet Revolution. Jan Hora matured into a leading Czech organist with a successful career worldwide. Olga Stolzová was a prominent eye doctor. These people testify to the importance of a quality environment for the development of character in the first two decades of one’s life.

Jaroslav Mihule has not lived a life in the spotlight – with the exception of his prorectorship, when he awarded Charles University Honorary Doctorates to the likes of Rudolf Firkušný or Petr Eben – but he is the salt of the earth, without whose inconspicuous efforts our country’s culture would be both poorer and less flavourful. May he continue to savour the joys and delights of life in a community that he has so effectively helped create!

A man without fear…

/ STANISLAVA STŘELCOVÁ

Dear Professor,

This major personal milestone is an extraordinary opportunity to express the respect that I have felt for you for many years. It was after 1989 that I was became more aware of your work and began to follow your activities both at home and abroad, amazed by the intensity of your efforts, from your microscopic focus in research and tuition to your popularising work and beyond. In your life, you have always managed to steer towards good and sensible goals, have served as a moral and expert authority to many of us, and have created a harmonious family with your wife.

As a child and an adolescent, I could avail myself of a family that taught me to recognise and discern what is creative and inventive from what is shallow and unimaginative. My parents, university teachers, were heirs of a First Republic mentality. My musicologist father helped me discover your publications back in the 1960s with your inspirational brochure Martinů in Pictures and your pocket biography of the composer, released in 1966. In the 1970s, when attending the Faculty of Arts in Brno, I was drawn most powerfully to the music of Leoš Janáček, although the Brno music scene gave prominence to the works of Bohuslav Martinů as well. The opera house, philharmonic concerts, the Friends of Music Circle, everything formed a highly favourable impression of the composer, thanks also to the enthusiasm of programmers and riveting artistic performances. I was especially captivated by your 1974 monograph on Bohuslav Martinů, which I got from my father: "It is a great work written by a fine musicologist and a good man", he said. I still have it. And with it of course your other books on Martinů and aesthetics in general. It was an important and sympathetic message to me at the time; I am convinced that even scholarly works reflect their author’s character as well as his education and erudition.

I first met you in person, Professor, sometime in the early 1990s thanks to the Bohuslav Martinů Foundation and its chairman, the composer Viktor Kalabis. You were also often mentioned in our conversations about music with his wife, the harpsichordist Zuzana Růžičková. And because were are influenced by both attitudes and verbal sentiments, my understanding was gradually fleshed out within the foundation by figures such as the composer O. F. Korte, the violinist Ivan Štraus, or the lawyer Richard Klos and the musicologist Jan Kapusta, who wrote a book about the incredible case of Martinů! Everyone spoke of you as a man without fear, although that was no easy trait to maintain under the former regime. You always stood bravely amidst the developments regarding Martinů, ever guiding them sensitively forwards.

Of major importance was your personal connection with the composer’s wife, the Frenchwoman Charlotte Martinů, who befriended you and whom you accompanied during her visits here. She was, in your words, a rare woman; after her husband’s death, she diligently cared for his legacy all over the world for almost twenty years, and she also aided his official recognition in Czechoslovakia. Through her efforts as much as others, we grew accustomed to the idea that the globe-trotting Bohuslav Martinů regarded himself as a Czech composer to the very end of his life…

My radio work allowed me to meet you at the microphone some years ago, Professor, and our main topic was again Bohuslav Martinů. Even as a secondary-school student after the war, you considered him to be an heir and defender of our democracy alongside Jan Masaryk. You concluded your studies at the Faculty of Education in Prague with a doctoral thesis on his symphonies. At the former Czechoslovak Radio, you had worked with enlightened employees from your student days, especially with the music director Dr Eduard Herzog. Your firm convictions gave uncertainty to your academic career. Yet all the same, you stayed loyal to Prague’s Charles University, and after 1989 you could finally realise your attitudes in academic functions as well, notwithstanding your continued activities as a musicologist and aesthetician. You accomplished much for our country and our music as a diplomat with UNESCO and as our ambassador in the Netherlands. You never forgot your everyday work on behalf of both Bohuslav Martinů and our music and nation, Professor. All throughout this, you followed the triune purpose of the Bohuslav Martinů Foundation, Institute, and Centre in Polička, and saw value in this cooperation.

During our interviews you humbly highlighted the works of others, although it was you who provided initiative and momentum to beneficial projects. Your fruitful life has yielded much success, you have always been true to yourself, strict yet kind and wise, building on humanist traditions, the substance of which you pass on to younger generations. I thank you for this with all my heart, and I wish you much health in the years to come.

A prelude for Jaroslav Mihule

/ JIŘÍ HLAVÁČ

Over the course of my life I have encountered many interesting and inimitable people. Besides their distinctive spiritual essence, some of them also had features that made them stand out from the rest. Karel Husa had a unique attachment to his mother tongue, a rich vocabulary, and delightfully soft articulation. Josef Suk was noted for the pliant gesticulation of his hands, which he presumably cultivated when playing the violin and viola. Luděk Bukač always maintained a somewhat detached perspective, possibly a vestige of the peripheral vision required in his days as a hockey player and coach. Věra Galatíková would often focus the depth of her gaze both at the opponent with whom she was debating and at the whole breadth of the auditorium, always checking what went on around her. Naděžda Kniplová kept up the appearance of a heroine and fateful protagonist just as much when off work at home as on the opera stage. Jaroslav Mihule has his typical smile, which reveals a wise and kind heart. But I was much more in touch with the excellent oboist and teacher, Professor Jiří Mihule, my colleague of many years at the Faculty of Music. He also wore the typical family smile at staff meetings of the wind department, and during entrance and final examinations. I often searched for a link between the two professors, with some success. Graceful manners and an ability to find prudent solutions to unpleasant situations, a sense of reality and an unaffected humility were among the qualities they shared. But Professor Jaroslav Mihule has one feature on top of that, presumably induced by his years-long participation not just in arts, but also in sports. Is that where he acquired his extraordinary perseverance and sustained productivity? Or even the smile, which is encouraging and amazingly relaxed, as is required for peak performance in sports? I do not know, I never asked him, even though I would love to know.

Dear Professor, there are long truths and short ones, and you know both. You know that life often asks no questions and simply likes to dictate. You have always accepted its demands with grace and a wonderful smile. May you keep both these qualities in all that you do, be it the music of Bohuslav Martinů, art, sports, or anything that is mundanely beautiful and beautifully mundane. Wishing you all that is good and kind, most sincerely, Jiří Hlaváč

Celebrating Jaroslav Mihule

/ MONIKA HOLÁ

Anyone with the slightest interest in Bohuslav Martinů and his music will know the name of Jaroslav Mihule, the musicologist who devoted a large part of his professional life to the study of Martinů.

Jaroslav Mihule is a leading Czech specialist on the life and works of Martinů. He devoted his whole life to the composer and has written more than 11 books on the subject, alongside a score of expert studies that discuss Martinů or connected topics. When Jaroslav Mihule’s first monograph Bohuslav Martinů. Profil života a díla (Profile of Life and Work) was published in 1974, it was without a doubt the most erudite source on the composer. The monograph prioritised a scholarly perspective on the composer’s legacy (his chronology and a detailed analysis of his oeuvre) and deliberately eschewed more minute biographical facts. In 2002 Mihule published an extensive new monograph titled Martinů. Osud skladatele (The Composer’s Fate). In it, the author expanded his initial work in a remarkable manner. Osud skladatele contains every last possible detail from the life and works of Martinů; the author compiles information from chronicles, registers, official documents, old issues of newspapers and magazines, or private correspondence, even drawing on previously unpublished manuscripts held in private collections. A full 15 years later, at the end of 2017, a revised version of the book was released. The lavishly printed publication combines all of the greatest qualities of Mihule’s previous works and further embellishes them with frequent illustrations.

The aforesaid publications are among the key works of Professor Mihule, but they are far from his only output. He has promoted the legacy of Bohuslav Martinů in a number of other ways: he co-founded the Bohuslav Martinů Society, he was on the board of Foundation Martinů, based in Basel, Switzerland, and he served as vice chairman of the Bohuslav Martinů Foundation in Prague; his linguistic capabilities (political circumstances caused him to take mandatory lessons in German and later Russian, to which he added of his own accord French, Latin, Ancient Greek, and English) predestined him to be invited to lecture at universities all around the world, and he also actively participated in global musicology conferences. Jaroslav Mihule was always tenured at the Faculty of Physical Education and Sport of Charles University in Prague, where he worked as a lecturer, assistant professor, senior lecturer, and professor. His academic career culminated in the 1990s, when he was elected to serve as Prorector of Charles University for two terms of office and in 1994 as Vice Dean of the Faculty of Education of Charles University. In 1991 he was also charged with representing the Czechoslovak Federal Republic in the UNESCO committee at the 26th congress in Paris as an expert on tertiary education, and in 1994–1997 he served as the first extraordinary and plenipotentiary ambassador of the Czech Republic to the Netherlands.

Professor Mihule’s accomplishments have been recognised by a number of awards, including the Gold Medal of Charles University in 1994, the Classic ’95 Award for lifetime achievements, Commemorative Diplomas from the Polička Municipal Authority and from the Faculty of Education of Charles University in 2015, and in 2018 the Annual Bohuslav Martinů Award for lifetime achievements in the scientific evaluation, dissemination, and application of the composer’s works, which is bestowed by the Bohuslav Martinů Foundation.

In May 2019 Jaroslav Mihule was declared an honorary citizen of Polička. This officially cemented his 60 years of close ties with the birthplace of Martinů. His first visits to the town took place when the composer’s sister Marie was still alive – and she personally assisted Mihule in his initial scholarly investigations in Polička. Professor Mihule also repeatedly travelled to the town after Martinů's, in the company of his widow, Charlotte. Many further visits took place over the years, whether “privately” in his capacity as musicological researcher or as a knowledgeable guide to members of the newly established Bohuslav Martinů Society in the 1970s. He contributed greatly to local culture by creating an exhibition of the life and works of the composer in the Bohuslav Martinů Centre in Polička, entitled The Colourful World of Bohuslav Martinů (2009-present). His genuine affinity for the locality is also evidenced by his donation of numerous rare objects from Martinů’s estate, which were passed on to Mihule by the composer’s widow – to name a few, a portion of the composer’s library, two albums of family photos, and last but not least, the vocal score of Martinů’s opera Juliette with handwritten markings by the composer himself. The Municipal Museum is immensely grateful for these donations, as they enrich its core Martinů collection in Polička.

The previous lines clearly testify to Jaroslav Mihule’s professional connection with the Polička-born composer. This kinship is further augmented by a double anniversary: 130 years since the birth of Bohuslav Martinů, Jaroslav Mihule is celebrating his 90th birthday (on 1 December), and the same major personal milestone is shared by his wife Alena, whose birthday falls directly to 8 December, the very same day as Martinů! This fact is aptly symbolic, as Mrs Mihulová has stood by her husband’s side since 1952 and has always provided him with the ideal support for his professional endeavours with indomitable enthusiasm (despite having to struggle to retain her grammar-school teaching post in the grim years of Communist oppression, which deemed her “insufficiently aware”, according to official documents).

Therefore, allow me – on behalf of all the employees of the Bohuslav Martinů Centre and the Municipal Museum in Polička – to wish Professor Mihule and his wife Alena all the best, as good health as ever, and to thank them most cordially for all they have done for culture and education.